Aikido is the study of aiki. Its not the study of jujutsu techniques from the 1800s, nor is it the refinement—or constant pursuit of—the most efficient fighting or competitive methods. It is the study of human movement between people and, by extension, the principles that remain just as relevant in our non-physical human interactions.

Those principles are everywhere: collision, conflict, timing, resistance, blending, centrifugal and centripetal force, and ultimately a refined attunement to another person—ki-musubi. The ability to “sense” movement isn’t mystical or mysterious. It comes from studying patterns and developing sensitivity to them over time.

You see this level of sensitivity in elite athletes. Muhammad Ali had it. Michael Jordan had it. Tiger Woods had it. Tom Brady had it. In the modern West, sports have become the primary arena where this level of skill is recognized and admired, so we naturally assume that this is the only place it can be developed.

Historically, that same sensitivity, timing, and attunement were recognized as valor, bravery, and martial competence. But that was in a world where survival, conflict, and violence were unavoidable features of daily life. As societies became more stable, civilized, and morally oriented, raw martial competence ceased to be a suitable aim for the vast majority of human beings. In fact, the opposite became true. Modern society does not need more war, domination, or physical conflict—it needs greater civility, moral guidance, restraint, and the ability to navigate tension without resorting to force.

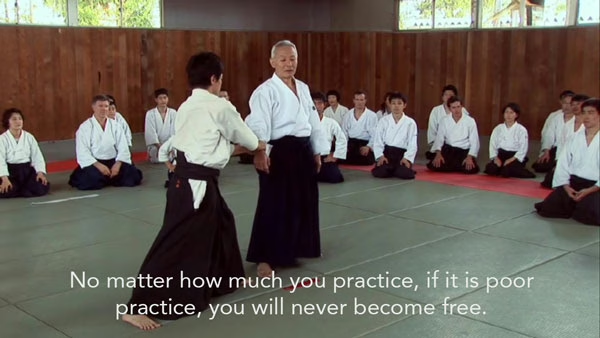

This perspective was clarified for me years ago by a remark made by Endo Seishiro Shihan during one of his early seminars in the United States, around 2005. Looking out at the room, he said:

“I see that many of you are practicing Aikido as a budo. However, I am practicing Aikido as an Aikido.”

Seishiro Endo Shihan

At the time, it sounded almost casual. Over the years, its meaning has only deepened.

He was not dismissing budo—a term broadly associated with martial disciplines shaped by combat, discipline, and moral cultivation. Rather, he was drawing a distinction of emphasis. Practicing Aikido as budo often frames the art through effectiveness, structure, lineage, and technical inheritance. Practicing Aikido as Aikido places the focus elsewhere: on the direct study of aiki itself.

That distinction matters. If Aikido is understood primarily as a historical fighting system, its value is judged largely on technical performance. In the current era—shaped heavily by social media and online video platforms—it is often judged by individuals who, despite their own claims, have not spent the time or effort that warrants or grants them any authority to present the art to the entire world for critique. The result is a shallow evaluation of a deep practice, assessed through fragments rather than lived experience. Patience, humility, and demonstrated technical competence—qualities traditionally cultivated through deep and lengthy study—are essential prerequisites before placing one’s interpretation of the art into the public arena.

If Aikido is instead understood as a method for studying connection, timing, resistance, and relationship at a fundamental level, then its relevance extends far beyond technique preservation or martial comparison.

Consider activities like golf, surfing, making art—or learning to play music. Each involves countless variables, most of them impossible to measure precisely. A musician does not simply execute notes; they develop timing, touch, phrasing, and responsiveness. When we listen to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, we don’t hear effort—we hear inevitability. What disappears from view is the discipline, repetition, and long refinement required to reach that level of expression.

That same essence is what people respond to in Aikido demonstrations. What often goes unseen is the time, patience, and sustained effort required to cultivate that level of refinement—just as in any serious pursuit.

Like those disciplines, if Aikido holds no meaning during the long process of learning it, then the practice itself becomes difficult to justify. And if the ideal is never fully realized, does that make the effort pointless? If one never shoots par, rides a perfect wave, composes enduring music, or creates widely appreciated art, does that invalidate the pursuit? Most people would say no—because the value lies in the practice itself, not only in the outcome.

Not everyone finds value in this kind of path. Sometimes it is a matter of timing. Sometimes expectations do not align. Sometimes people are simply not looking for a long-term practice or a “quest” of this sort. And sometimes the teaching or environment is not the right fit. All of that is natural.

These questions are not unique to Aikido, but Aikido brings them into focus. For that reason, it is important for a dojo or community to be clear about the purpose of its practice and to remain consistent with it. Those who are drawn to it will stay. Those who are not will find something else that suits them better. We do not need universal appeal—only enough committed practitioners to keep the doors open and continue practicing forward.